- MEDIA

- MOST OR LEAST PROTECTED FOREST?

Most or least protected forest?

- Article

- Wood products

EU Member States report on measures to protect forests and nature in various ways. Sweden stands out with its very strict view of what constitutes protection. “As a result of this, Sweden appears to be the worst in Europe; however, were we to report in the same way as many other countries, we would be viewed as a pioneer. The same problem applies to how we report the status of different habitats, something that can have major consequences for how we can cultivate Swedish forests in future,” says Linda Eriksson, Forest Director at the Swedish Forest Industries Federation.

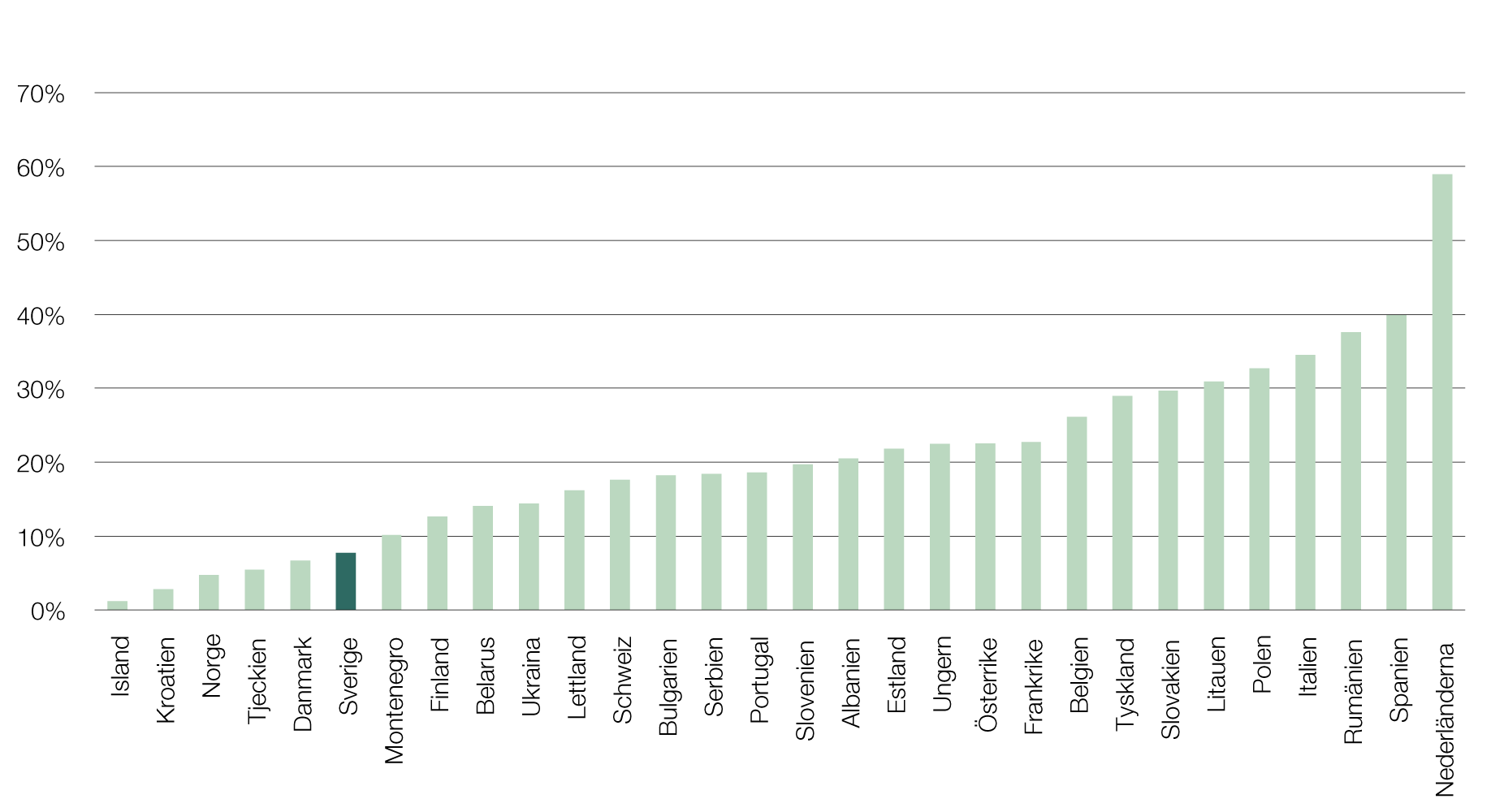

Percentage of protected forest area according to FRA2020 (FAO) and Forest Europe

The tone of debate on forestry has become harsher over recent years. One much-discussed issue is how much forest Sweden actually protects compared to other countries. There have been comments such as that Sweden is “among the dregs” and that we “have a long way to go” before we can even begin to measure ourselves against the top-ranked countries.

“That’s correct. If one chooses to compare reported figures, Sweden is a long way down the rankings. However, if one takes into account that our Swedish agencies report on protected nature in a different, stricter way than the rest of Europe, the situation is quite different,” notes Linda Eriksson, Swedish Forest Industries Federation.

So, that are the differences when it comes to reporting on protected forests?

"Sweden only reports formal protection within a nature reserve, national park, Natura 2000 area or biotope protection area. Combined, these constitute just over 14 per cent of Sweden’s area. However, we do not report on the large area of forest voluntary set aside, non-productive land, protected shoreline and other areas that are protected in various ways.

Most EU Member States state that they protect at least 20 per cent and several report that one third of their land area is protected. But their requirements for designating an area as protected are nowhere near as strict as Sweden’s. Much of the area they count is covered by forms of protection that actually allow agriculture and forestry. It’s really like comparing apples and oranges.

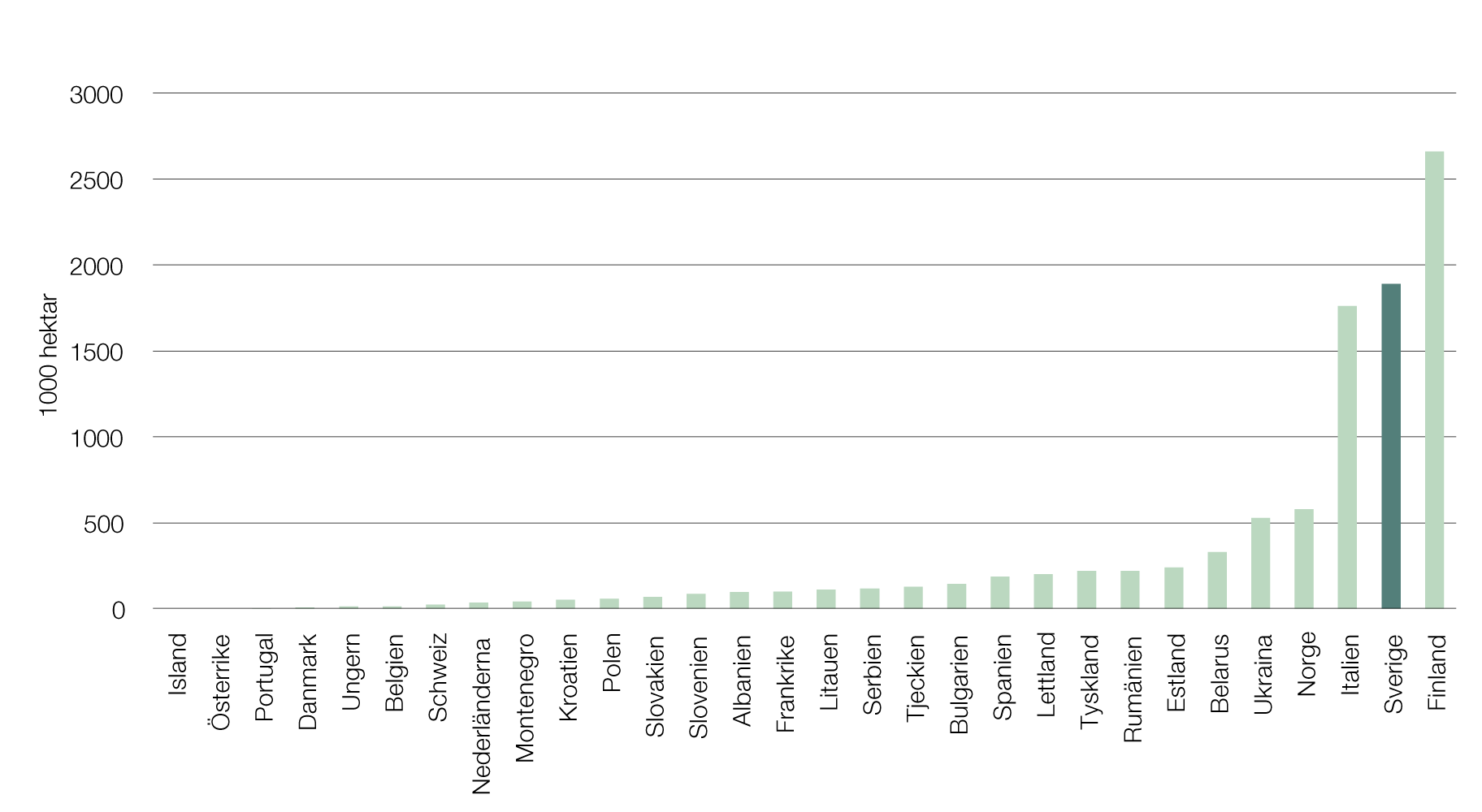

You would get a completely different result if the comparison were based on the same strict definition of protection that Sweden uses in its reporting, in which case Sweden and Finland would be the top-ranked countries in Europe.”

How does reporting work when it comes to the status of different habitats?

“Here, the crucial thing is which reference year and reference area one uses for different types of habitat. Here too Sweden has chosen to deviate, with stricter reporting criteria. In Sweden, the present situation is compared with assumed pre-industrial conditions, i.e., the mid-nineteenth century. Many other countries compare the current prevalence of habitat types with the year they joined the EU, so over 100 years after Sweden’s chosen reference year. This provides completely different conditions, as reflected in the figures reported.

In relation to other countries, Sweden reports a very low percentage of land with protected status, but this too is like comparing apples and oranges. We consider Sweden’s methodology to be unreasonable. Were we to report in the same way as other countries, here too we would be at the top of the rankings.”

Area of protected forest in classes 1.1 and 1.2 according to Forest Europe (thousand hectares)

Source: Hannerz & Simonsson 2023 based on data from Forest Resources Assessment (FAO).

How has it come about that countries report data to the EU in different ways?

“The reporting regulations are not specific enough, something that is now proving to be very unfortunate. Countries have different traditions and different tools for protecting nature and, when it comes to reporting to the EU, they do so in the same way they have always done at national level. The regulatory framework is interpreted in different ways; even the term forest may be defined differently.”

What consequences does this have?

“Reported figures have been widely disseminated in the forest policy debate and it’s clearly a problem when Swedish forestry is presented in a bad light. But future reporting may have enormous consequences on a purely practical level. When the EU enacts new legislation, it can have an impact on how we are permitted to manage our forests. For example, the proposed nature restoration law may force us to restore large areas of forest that we will then not be permitted to cultivate. How we report on the status of habitats will have a major impact on what size of area this applies to.

Then there is the Convention on Biological Diversity, which states that 30 per cent of the Earth’s surface should be protected at a global level, of which 10 per cent must be under strict protection. So, of course, it is important how one defines and measures what is protected.”

What changes would the Swedish Forest Industries Federation like to see?

“While we are in favour of international targets for biodiversity and protected nature, if these requirements become legally binding we need regulation to ensure that all countries’ reporting is as comparable as possible. Sweden must continue to have high ambitions for biodiversity but we need the retain our mandate to decide what we want to protect and how to do it. Under the present system, we leave many of these decisions to the EU.

The Swedish Forest Industries Federation believes that Sweden should change how it reports. We are working to inform politicians about the situation as things stand and what the consequences will be, as awareness of these issues is fairly low. Politicians need to understand the big picture and guide government agencies on how Sweden should be reporting.”

Are there any changes underway?

“Some processes are ongoing, so there is some hope. For example, the Government has tasked the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency with investigating which reference areas we should use when reporting on habitats, while the All-Party Committee on Environmental Objectives is to propose an overall strategy for meeting Sweden’s international commitments in a cost-effective manner.”

Text: Kerstin Olofsson

Photo: Björn Leijon